Reading List

The most recent articles from a list of feeds I subscribe to.

Comforting Myths

In several recent posts, I've attempted to address how the structure of standards bodies, and their adjacent incubation venues, accelerates or suppresses the potential of the web as a platform. The pace of progress matters because platforms are competitions, and actors that prevent expansions of basic capabilities risk consigning the web to the dustbin.

Inside that framework, there is much to argue over regarding the relative merits of specific features and evolutionary directions. This is healthy and natural. We should openly discuss features and their risks, try to prevent bad consequences, and work to mend what breaks. This competitive process has made browsers incredibly safe and powerful for 30 years.

Until iOS, that is.

Imagine my surprise upon hearing that Apple isn't attempting to freeze the web in amber, preserving advantages for its proprietary platform, and that it instead offers to redesign proposals it disagrees with.

As I have occasionally documented, this has not been my experience. I have relatively broad exposure to the patterns of Apple's collaboration, having designed, advised on, or led teams that built dozens of features across disparate areas of the platform since the Blink fork.1

But perhaps this was the wrong slice from which to judge? I've been hearing of Apple's openness to collaboration on challenging APIs so often that either my priors are invalid, or something else is at work. To find out, I needed data.

Background

A specific parry gets deployed whenever WebKit's sluggish feature pace comes up: “controversial” features “lack consensus” or “are not standards” or “have privacy and security problems” (unspecified). The corollary being that Apple engages in good-faith to address these developer needs in other ways, even in areas where they have overtly objected.

Apple's engine has indisputably trailed Blink and Gecko in all manner of features over the past decade. This would not be a major problem, except that Apple prevents other browsers from delivering better and more competitive web engines on iOS.

Normally, consequences for not adopting certain features arrive in the market. Browsers that fail to meet important needs, or drop the ball on quality lose share. This does not hold on iOS because no browser can ship a less-buggy or more capable engine than Apple's WebKit.

Because competitors are reduced to rebadging WebKit, Apple has created new responsibilities and expectations for itself.2 Everyone knows iOS is the only way to reach wealthy users, and no browser can afford to be shut out of that slice of the mobile market. Therefore, the quality and features of Apple's implementation matter greatly to the health and competitiveness of the web.

This put's Apple's actions squarely in the spotlight.

Is Apple Engaged In Constructive API Redesign?

It's possible to size up Apple's appetite for problem-solving in several ways. We can look to understand how frequently Apple ships features ahead of, or concurrently with, other engines because near-simultaneous delivery is an indicator of co-design. We can also look for visible indications of willingness to engage on thorny designs, searching for counter-proposals and shipped alternatives along the way.

General Trends

This chart tracks single-engine omissions over the past decade; a count of designs which two engines have implement but which a single holdout prevents from web-wide availability:

Safari consistently trails every other engine, and APIs missing from it impact every iOS browser.

Thanks to the same Web Features data set, many views are possible. This data shows that there are currently 178 features in Chromium that are not available in Safari, and 34 features in Safari that are not yet in Chromium. (or 179 and 37 for mobile, respectively). But as I've noted previously, point-in-time evaluations may not tell us very much.

I was curious about delays in addition to omissions. How often do we see evidence of simultaneous shipping, indicating strong collaboration? Is that more or less likely than leading vendors feeling the need to go it alone, either because of a lack of collaborative outreach, or because other vendors do not engage when asked?

To get a sense, I downloaded all the available data (JSON file), removed features with no implementations, removed features introduced before 2015, filtered to Chrome, Safari, and Firefox, then aggregated by year. The resulting data set is here (JSON file).

The data can't determine causality, but can provide directional hints:

Leading Launches by Year

Features Shipped Within One Year of the Leader

Features Shipped Two+ Years After the Leader

Safari rarely leads, but that does not mean other vendor's designs will stand the test of time. But if Apple engages in solving the same problems, we would expect to see Safari leading on alternatives3 or driving up the rates of simultaneously shipping features once consensus emerges. But these aren't markedly increased. Apple can, of course, afford to fund work into alternatives for “problematic” APIs, but it doesn't seem to.

Narratives about collaboration in tricky areas take more hits from Safari's higher incidence of catch-up launches. These indicate Apple shipping the same design that other vendors led with, but on a delay of two years or more from their first introduction. This is not redesign. If there were true objections to these APIs, we wouldn't expect to see them arrive at all, yet Apple has done more catching up over the past several years than it has shipped APIs with other vendors.

This fails to rebut intuitions developed from recent drops of Safari features (1, 2) composed primarily of APIs that Apple's engineers were not primary designers of.

But perhaps this data is misleading, or maybe I analysed it incorrectly. I have heard allusions to engagement regarding APIs that Apple has publicly rejected. Perhaps those are where Cupertino's standards engineers have invested their time?

Hard Cases

Most of the hard cases concern APIs that Apple (and others) have rightly described as having potentially concerning privacy and security implications. Chromium engineers agreed those concerns have merit and worked to address them; we called it “Project Fugu” for a reason. In addition to meticulous design to mitigate risks, part of the care taken included continually requesting engagement from other vendors.

Consider the tricky cases of Web MIDI, Web USB, and Web Bluetooth.

Web MIDI

Apple has supported MIDI in macOS for at least 20 years — likely much longer — and added support for MIDI on iOS with 2010's introduction of Core MIDI in iOS 4.2. By the time the first Web MIDI proposals broke cover in 2012, MIDI hardware and software were the backbone of digital music and a billion dollar business; Apple's own physical stores were stocking racks of MIDI devices for sale. Today, an overwhelming fraction of MIDI devices explicitly list their compatibility with iOS and macOS.

It was therefore a clear statement of Apple's intent to cap web capabilities when it objected to Web MIDI's development just before the Blink fork. The objections by Apple were by turns harsh, condescendingly ignorant and imbued with self-fulfilling stop-energy; patterns that would repeat post-fork.

After the fork and several years of open development (which Apple declined to participate in), Web MIDI shipped in Chromium in early 2015. Despite a decade to engage, Safari has not shipped Web MIDI, Apple has not provided a “standards position” for it4, and has not proposed an alternative. To the best of my knowledge, Apple have also not engaged in conversations about alternatives, despite being a member of the W3C's Audio Working Group which has published many Working Drafts of the API. That group has consistently included publication of Web MIDI as a goal since 2012.

Across 11 charters or re-charters since then, I can find no public objection within the group's mailing list from anyone with an @apple.com email address.5 Indeed, I can find no mentions of MIDI from anyone at Apple on the public list. Obviously, that is not the same thing as agreeing to publication as a Recommendation, but it also not indicative of any attempts at providing an alternative.

But perhaps alternatives emerged elsewhere, e.g., in an Incubation venue?

There's no counter-proposal listed in the WebKit explainers repository, but maybe it was developed elsewhere?

We can look for features available behind flags in Safari Technology Preview and read the Tech Preview release notes. To check them, I used curl to fetch each of the 127 JSON files that are, apparently, the format for Safari's release notes, pretty-printed them with jq, then grepped case-insensitively for mention of “audio” and “midi”. Every mention of “audio” was in relation to the Web Audio API, the Web Speech API, WebRTC, the <audio> element, or general media playback issues. There were zero (0) mentions of MIDI.

I also cannot locate any public feedback on Web MIDI from anyone I know to have an @apple.com email address in the issue tracker for the Web Audio Working Gropup or in WICG except for a single issue requesting that WICG designs look “less official.”

The now-closed Web MIDI Community Group, likewise, had zero (0) involvement by Apple employees on its mailing list or on the successor Audio Community Group mailing list. There were also no (0) proposals covering similar ground that I was able to discern on the Audio CG issue list.

Instead, Apple have issued a missive decrying Web MIDI as a privacy risk. As far as anyone can tell, this was done without substantive analysis or engagement with the evidence from nearly a decade of deploying it in Chromium-based browsers.

If Apple ever offered an alternative, or to collaborate on a redesign, or even an evidence-based case for opposing it,6 I cannot find them in the public record.7

Web USB

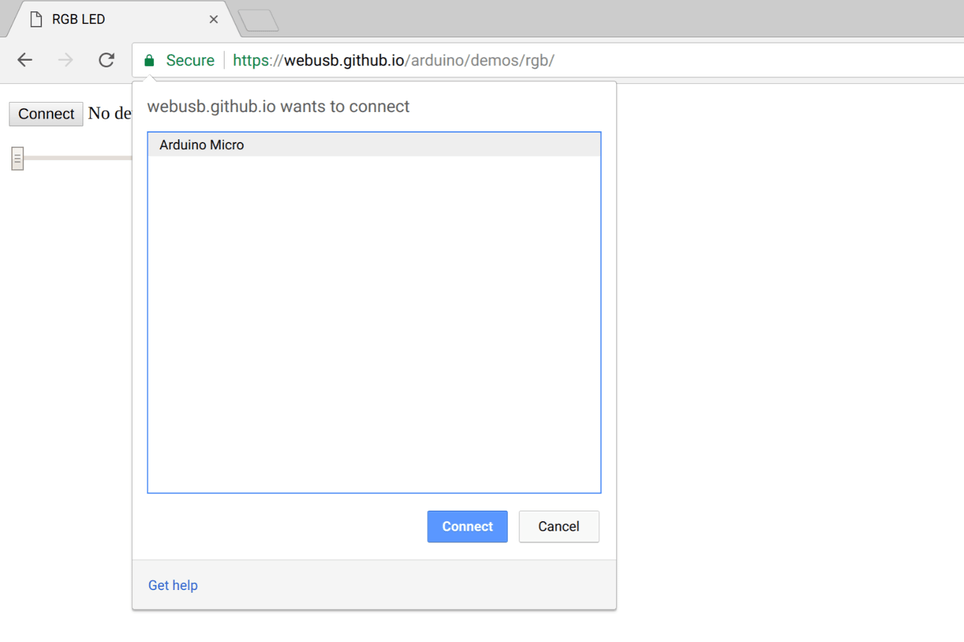

USB is a security sensitive API, and Web USB was designed with those concerns in mind. All browsers that ship Web USB today present “choosers” that force users to affirmatively select each device they provide access to, from which sites, and always show ambient usage indicators that let users revoke access. Further, sensitive device classes that are better covered by more specific APIs (e.g., the Filesystem Access API instead of USB Mass Storage) are restricted.

This is far from the Hacker News caricature of "letting any web page talk to your USB devices," allowing only point connections between individual devices and sites, with explicit controls always visible.

After two years of public development and a series of public Origin Trials lasting seven months (1, 2), the first version of the API shipped in Chrome 61, released September 2017.

I am unable to locate any substantive engagement from Apple about alternatives for the motivating use-cases outlined in the spec.

With many years of shipping experience, we can show that these needs have been successfully addressed by WebUSB; e.g. teaching programming in classrooms. More than a decade after it was first approached about them, it's unclear what Apple's alternative is. Hollowing out school budgets to buy Cupertino's high-end devices to run unsafe, privacy-invading native apps?

Apple have included Web USB on the list of APIs they “decline to implement” and quite belatedly issued a “standards position” opposing the design. But no alternative proposal was developed or linked from those threads, despite being asked directly if there might be more palatable alternatives.

I can locate no appetite from Apple's standards engineers to address these use-cases, know of no enquiries into data about our experiences shipping them, and can find no constructive counterproposals. Which raises the obvious question: if Apple does engage to develop counterproposals in tricky areas, how long are counterparties meant to wait? More than eight years?

Web Bluetooth

Like Web USB, Web Bluetooth was designed from the ground-up with safety in mind and, as a result, has been incredibly safe and deployed at massive scale for eight years. It relies on the same chooser model in Chromium-based browsers.

As with all Project Fugu device APIs, Web Bluetooth was designed to reduce ambient risks — no access to Bluetooth Classic, available only on secure sites, and only in <iframe>s with explicit delegation, etc. — and to give implementers flexibility about the UIs they present to maximise trust and minimise risk. This included intentionally designing flexibility for restricting access based on context; e.g., only from installed PWAs, if a vendor chooses that.

The parallels with Web USB continue on the standards track. I can locate no engagement from any @apple.com or @webkit.org email addresses on the public-web-bluetooth mailing list. In contrast, when design work began in 2014 and every browser vendor was invited to participate, Mozilla engaged. I can find no evidence of similar openness on the part of Apple, nor constructive counter-proposals.

Over more than three years of design and gestation in public, including very public Origin Trials, Apple did not provide constructive feedback, develop counter-proposals, or offer to engage in any other way I can find.

This appears to be a pattern.

From a deep read of the “standards position” threads for designs Apple opposes, I cannot find evidence that Cupertino has ever offered a constructive counter-proposal for any API it disfavours.

These threads do demonstrate downplaying clearly phrased developer needs, rather than proactive engagement, and it seems the pattern is that parties must beg Apple to belatedly form an opinion. When there is push-back, often after years of radio silence, requesters (not Apple) also have to invent potential alternatives, which Apple may leave hanging without engagement for years.

Worse, there are performative expressions of disinterest which Apple's standards engineers know are in bad-faith. An implementer withholding engagement from a group, then claiming a lack of implementer engagement in that same venue as a reason not to support a design, is the sort of self-serving, disingenuous circularity worthy of disdain.

Overall Impressions

Perhaps both the general trends and these specific high-profile examples are aberrant. Perhaps Apple's modus operandi isn't to:

- Ignore new incubations, even when explicitly asked to participate.

- Fail to register concerns early and collaboratively, where open design processes could address them.

- Force web developers and other implementers to request “positions” at the end of the design process because Apple's disengagement makes it challenging to understand Cupertino's level of support (or antipathy).

Mayhaps it's not simply the predicable result of paltry re-investments in the web by a firm that takes eye watering sums from it.

If so, I would welcome evidence to that effect. But the burden of proof no longer rests with me.8

What's Happening Here?

It's hard to say why some folks are under the impression that Apple are generous co-designers, or believe Apple's evocative statements about hard-case features are grounded in analysis or evidence. We can only guess at motive.

The most generous case I can construct is that Apple's own privacy and security failures in native apps have scared it away, and that spreading FUD is cover for those sins. The more likely reality is that upper management fears PWAs and wants to keep them from threatening the App Store with safe alternatives that don't require paying Apple's vig.

Whatever the cause, the data does not support the idea that Apple visibly engages in constructive critique or counter-proposal in these areas.

Moreover, it shows that many of Apple's objections and delays were unprincipled. It should be every browser's right to control the features it enables, and Cupertino is entirely within those rights to avoid shipping features in Safari. But the huge number of recent “catch-up” features tells a story that aligns more with covering for embarrassing oversights, rather than holding a line on quality, privacy, or security.

On the upside, this suggests that if and when web developers press hard for capabilities that have been safe on other platforms, Cupertino will relent or be regulated into doing so. It scarcely has a choice while simultaneously skimming billions from the web and making arguments like these to regulators (PDF, p35):

The moment iPhone users around the world can install high-quality browsers, the conversational temperature about missing features and reliability will drop considerably. Until then, it remains important that Apple bear responsibility for the problems Apple is causing not only for Apple, but for us all.

FOOTNOTES

My various roles since the Blink fork have included:

- TC39 representative

- Co-designer of Service Workers ('12-'15)

- Co-Tech Lead for Project Fizz ('14-'16)

- Three-time elected member of the W3C's Technical Architecture Group ('13-'19)

- Web Standards Tech Lead for Chrome ('15-'21)

- Co-Tech Lead for Project Fugu ('17-'21)

- Co-designer of Isolated Web Apps ('19-'21)

- Blink API OWNER ('18-present)

- Ongoing advisor to Edge's web standards team

In my role as TAG member, Fizz/Fugu TL, and API OWNER I've designed, reviewed, or provided input on dozens of web APIs. All of this work has been collaborative, but these positions have given me a nearly unique perch from to observe the ebb and flow of new designs from, particularly on the "spicy" end of the spectrum. ⇐

Apple has many options for returning voluntarity to the market for iOS browsers.

Most obviously, Apple can simply allow secure browsers to use their own engines. There is no debate that this is possible, that competitors generally do a better job regarding security than Apple, and that competitors would avail themselves of these freedoms if allowed.

But Apple has not allowed them.

Open Web Advocacy has exhaustively documented the land mines that Apple has strewn in front of competitors that have the temerity to attempt to bring their own engines to EU users. Apple's choice to geofence engine choice to the EU, indefensible implementation roadblocks, poison-pill distribution terms, and the continued prevarications and falsehoods offered in their defence, are choices that Apple is affirmatively and continually making.

Less effectively, Apple could provide runtime flags for other browsers to enable features in the engine which Apple itself does not use in Safari. Paired with a commitment to implement features in this way on a short timeline after they are launched in other engines on other OSes, competing vendors could risk their own brands without Apple relenting on its single-implementer demands. This option has been available to Apple since the introduction of competing browsers in the App Store. As I have argued elsewhere, near-simultaneous introduction of features is the minimum developers should expect of a firm that skims something like $19BN/yr in profits from the web (a ~95% profit rate, versus current outlays on Safari and WebKit).

Lastly, Apple could simply forbid browsers and web content on iOS. This policy would neatly resolve the entire problem. Removing Safari, along with every other iOS browser, is intellectually and competitively defensible as it removes the “special boy” nature of Safari and WebKit. This would also rid Apple of the ethical stain of continuing to string developers and competitors along within standards venues when it is demonstrably an enemy of those processes. ⇐

Apple regularly goes it alone when it is convinced about a design. We have seen this in areas as diverse as touch events, notch CSS, web payments, "liquid glass" effects, and much else. It is not credible to assume that Apple will only ship APIs that have an official seal of an SDO given Cupertino's rich track record of launch-and-pray web APIs over the years. ⇐

In fairness to Apple regarding a "standards position" for Web MIDI, the feature predates Apple's process. But this brings up the origin of the system.

Why does this repository exist? Shouldn't it be rather obvious what other implementers think of that feature, assuming they are engaged in co-design?

Yes, but that assumes engagement.

Just after the Blink fork, a series of incidents took place in which Chromium engineers extrapolated from vaguely positive-sounding feedback in standards meetings when asked about other vendor's positions as part of the Blink Launch Process. This feedback was not a commitment from Apple (or anyone else) to implement, and various WebKit leaders objected to the charachterisations. As a way to avoid over-reading tea leaves in the absence of more fullsome co-design, the "standards position" process was erected in WebKit (and Gecko) so that Chromium developers could solicit "official" positions in the many instances where they were leading on design, in lieu of clearer (tho long invited) engagement.

If this does not sound like it augurs well for assertions that Apple engages to help shape designs in a timely way...well, you might very well think that. I couldn't possibly comment. ⇐

There may have been Formal Objections (as defined by the W3C process) in private communications, but Member Confidentiality at the W3C precludes me from saying either way. If Apple did object in this way, it will have to provide evidence of that objection for the public record, as I cannot. ⇐

Apple's various objections to powerful features have never tried to square the obvious circle: why are camera and microphone access (via

getUserMedia()) OK, but MIDI et. al are not? What evidence supports the notion that adding chooser-based UIs will lead to pervasive privacy issues that cannot be addressed through mechanisms like those Apple is happy to adopt for Geolocation? Why, despite their horrendous track records, are native apps the better alternative? ⇐Mozilla objected to Web MIDI on various grounds over the years, and after getting utterly roasted by its own users over failing to support the API, shipped support in Firefox 108 (Dec '22).

The larger question of Mozilla's relationship to device APIs was a winding road. It eventually culminated (for me) in a long discussion at a TAG meeting in Stockholm with EKR of TLS and Mozilla fame.

By 2016, Mozilla was licking its wounds from the failure of Firefox OS and retrenching around a less expansive vision of the future of the web. Long gone were the aspirations for "WebAPIs". Just a few short years earlier, Mozilla would have engaged (if not agreed) about work in this space, but an overwhelming tenor of conservativism and desktop-centricity radiated from Mozilla by the time of this overlapping IETF/W3C meeting.

It didn't make the notes, but my personal recollection of how we left things late in the afternoon in Stockholm was EKR claiming that bandwidth for security reviews was the biggest blocker that and that it was fine if we (Chromium) went ahead with these sorts of designs to prove they wouldn't blow up the world. Only then would Mozilla perhaps consider versions of them.

True to his word, Mozilla eventually shipped Web MIDI on EKR's watch. If past is prologue, we'll only need to wait another three to five years before Web Bluetooth et al. join them. ⇐

My memory is famously faulty, and I have been engaged in a long-running battle with Apple's legal folks relating to the suppression of browser choice on iOS. All of that colours my vision, and so here I have tried to disabuse myself of less generous notions by consulting public evidence to support Apple's case.

From what I was able to gather over many hours was overwhelmingly inculpatory. It is not possible from reading these threads and data points — rather relying on my own recollections — to sustain a belief that Apple have either provided timely constructive feedback on tricky APIs, or worked to solve the problems they address. But I am, in the end, heavily biased.

If my conclusions or evidence are wrong, I would very much appreciate corrections; my inbox and DMs are open.

If reliable evidence is provided, I will update this blog post to include it, and I encourage others to post on this topic in opposition to my conclusions. It should not be hard for Apple to make the case, assuming there is evidence to support it, that I've missed important facts. It would have both regulatory and persuasive valence regarding questions I have raised relating to Apple's footprint in the internet standards community. ⇐

Web Standards and the Fall of the House of Iamus

Commentary about browsers and the features they support is sometimes pejorative towards pre-standardisation features. Given Apple's constriction of Mozilla's revenue stream and its own strategic under-funding of WebKit, this usually takes the form "Chromium just ships whatever it wants."

This is true, of course, but not in the way commenters intend; and not only because Blink's rigorous launch process frequently prevents unvalidated designs from shipping.

Except for iOS, where Apple attempts to hide its role in undermining the competitive foundation of web standards, every vendor always ships "whatever it wants." That is the point of voluntary standards, and competition is the wind in those sails.

Working Groups don't gate what browsers ship, nor do they define what's useful or worthy. There are no seers; no Delphic oracles that fleetingly glimpse a true logos. Working Groups do not invent the future, nor do they hand down revealed truths like prophets of the House of Iamus.

In practice, they are thoughtful historians of recent design expeditions, critiquing, tweaking, then spreading the good news of proposals that already work through Web Standards ratified years after features first ship, serving to licence designs liberally to increase their spread.

In the end, this is the role of standards and the Working Groups that develop them: to license patents that read on existing designs, reducing risks to implementers who adopt them.

Anyone who tries to convince you otherwise, or invites you to try your hand at invention within a chartered Working Group, does not understand what those groups are designed to do. Sadly, this includes some folks who spend a lot of time in them.

Complaints about certain engines leading reveals a bias to fighting the last-war; fear of a return to the late 90s, when “irrational exuberance” applied not just to internet stocks, but also browser engines.

Unfounded optimism about our ability to deal with externalities of shipping prior to consensus created a great deal of pain. Misreadings of how browsers evolve in practice over-taught lessons that still invoke fear. But we have enough miles on the tires to see that standards aren't what create responsible feature development; thoughtful launch processes are.1

As we will see, consensus is never a precondition for shipping, nor could it be. If it were, nothing would move forward, for it is the threat (and sometimes reality) of popular features shipping without a priori agreement that brings parties to the table. It's also the only reliable defence against the fifth column problem.

Terminology Traps

Before we get into the role of the charters that define Standards Development Organisation (SDO) Working Groups, we must define some terms:2

- Proposal

- Any design, in any sort of document (Specification, Explainer, or scrawl on the back of a napkin) offered inside an SDO for standardisation. Proposals are revised through collaborative processes which function best inside SDOs thanks to carve-outs in competition laws allowing competitors to collaborate in writing standards.

- Proposals are implemented, and even shipped, well ahead of formal status as Web Standards in order to gain developer feedback, iterate on designs, and build confidence that they meet needs effectively.3

- Specification

- A document that describes the properties of an implementation, often in technical shorthand (e.g., Web IDL) and with reference to other specifications.

- Specifications are by and for implementers, rather than working web developers, and are the documents to which the IPR commitments of Web Standards attach.

- Explainer

- An overview of a proposal. Explainers are not specifications, but encapsulate the key points of designs in terms of the problems they solve.4 The goal is to explain the why along with the what, in terms web developers can weigh.

- In well-incubated designs, Explainers evolve in parallel to specifications. This forces API designers to think like web developers. Explainers serve as foci for considering alternatives and as well as “missing manuals” for early designs.

- Web Standard

- A specification that has been put forward by a chartered Working Group to the full membership, and granted official status after ratification. For example, by receiving the status as a Recommendation of the W3C by a vote of the Advisory Committee, or in the case of ECMA TC39, publication of an International Standard at ISO.

- Web standards create clarity around IPR concerns which pre-standards specifications cannot. These commitments license the patents of parties participating in a Working Group under Royalty Free terms.

- In practice, this also commits major firms to the defence of potential implementers, reducing risks across the ecosystem.

- Standards Track

- A specification document is "on the standards track" if its developers have signalled interest in formal, chartered Working Groups taking up their design for publication as a Web Standard, subject to clarification along the way. It is not necessary for any specific Working Group to agree for this description to hold.

- Designs in this state often carry IPR grants, but provide less patent clarity ("contribution only") than official Web Standards.

- Incubation

- Any process outside a chartered Working Group in which web developers, browser vendors, and other interested parties meet to understand problems and design solutions. Drafts of incubated designs are often volatile. Eventually, if a problem is judged important by participants, one or more designs congeal into brief, high-level "Explainers".

- Before features launch without flags in stable-channel browsers, developer and implementer feedback can lead to large changes in incubated designs. Designers and participants must actively solicit input and respond to substantive feedback constructively.

Proposals whose specifications receive formal status within SDOs are described as “adopted”, “recommended”, or “ratified”. This process binds the intellectual property of chartered Working Group participants to the licensing regime of the SDO by approval of the membership.

From this we can see that is nonsensical to discuss “proposals” and "standards" in the same breath. They are a binary pair. A specification has either one status or the other; it cannot be both.

No design that becomes a standard can start as anything but a proposal,5 and the liminal space of non-standard proposal is not somehow less-than or an aberration. Rather, it is an embryonic stage every design must pass through, and which every de jure Web Standard has taken at some point.

Armed with better language, we can develop an understanding of how features actually come to the web. Through this, we'll see why our optimism for standards has to come from our own powers of collaborative problem-solving, rather than waiting for designs to be handed down from Olympus.

Standardisation != Interoperability

Jake Archibald pointed out that linguistic precision is uncommon, and developers use the phrase “standard” or “web standard” loosely; a shorthand for features they can use without worry. That ground covers both official Web Standards and de facto standards. The example of WebP was raised, and was even more instructive than I recalled.6

A brief refresher: WebP was introduced by Google in 2010, shipping in Chromium in 2011. At that point, and for many years thereafter, WebP was not a standard. A high-level specification broke cover in 2012, but was not brought to an SDO. Patent rights and other IP questions were addressed only by Google's waiver and the Open Source licensing of libwebp.

Nearly all Chromium-based browsers adopted WebP by 2012. Microsoft Edge added support in 2018, Firefox joined the party in 2019, and Safari added support in 2020.

It was not until April 2021, a full decade after the format's introduction and after all major engines supported it, that WebP arrived at the IETF for standardisation. It finally earned RFC status in November 2024, four years after Apple unlocked wide compatibility, having been the last hold-out.

WebP gained tremendous adoption despite not being a standard for nearly 15 years. This has led some to suggest it was a Web Standard, as it had many of the properties expected of successful standards. Namely:

- Broad adoption. All major engines gained support before standardisation began in earnest.

- Stability. Despite adding opacity and animation later, every WebP image produced across the life of the format still renders correctly.

- Interoperability. The same WebP images work across implementations.

- IPR clarity. As the primary contributor to the format and reference implementation, Google's substantial legal and patent assets provided adopters with assurances related to the provenance of both the code and the codec fundamentals.

Many assume that Web Standards are the only path to achieving these attributes, but WebP shows us that this is mistaken. Web Standards deliver these properties most effectively and reliably, but WebP shows us that “being a standard” is not a requirement for interoperable implementation at scale, even in browsers.

Interoperability and adoption are, by inspection, independent of official status. Many formal Web Standards have spotty adoption or fail to achieve interoperability. The web also has a long history of de facto behaviours gaining official status long after interoperability and stability manifest in the market. This sits comfortably with the reality that every single web feature is non-standard for some fraction of its lifetime. At the limit, that fraction can be rather large.

Conflation of de facto standards, official Web Standards, wide deployment, and interoperability are likely to persist. However, those of us who work on browsers can and should be more precise, preferring “interoperability”, “widely deployed”, and “standards track” to “Web Standard” when those are more appropriate.

Standardisation != Responsibility

If we admit, as we must, that all features begin as non-standard proposals which proceed through official processes to become Web Standards, quality is never as simple as “standard good, non-standard bad.” A design can pass unaltered through every lifecycle stage without change to its technical shape or merits, and questions of wide implementation and interoperability are clearly extrinsic to the status of a design within an SDO.

We must locate definitions of relative goodness in more directly descriptive properties. I have given a few above, namely adoption, stability, interoperability, and IPR clarity. For a full account, we need to cover design-time attributes, including testability, specification rigour, wide review, and responsiveness to developer feedback . Taken together, they define what it means to solve important problems well on the standards track.

Developers and implementers weigh up these properties when judging APIs. Some designs, like WebP,7 can score highly on everything but adoption. WebP was not technically worse in 2015 than in 2019, or 2020, or 2024; only less widely adopted. Working web developers were free to exploit its benefits the whole time. Many did, and because it had been responsibly developed, interoperability followed, even before a proposal had been submitted to an internet standards body.

Likewise, we cannot judge other APIs shipped in a single engine to be low-quality on the basis of SDO status. Nor can we credit statements opposing them on that basis, particularly from parties that have not offered counterproposals. A single implementation may preclude features from becoming standards, but that says nothing about design fitness, or even prospects for eventual adoption.

This understanding draws our focus away from formal SDO status and toward more important properties of features. It also helps us weigh up the processes that gestate them:

- Are they friendly and open to developers, or are they smoke-filled rooms where old-timers hold sway?

- Do they encourage new work at the pace of emerging developer needs, or are they artificially constricted by a proliferation of veto players?

- Do those processes generate good tests and strong specifications, or do a few powerful editors regularly cut corners?

- Are features submitted for wide review to competent and responsive experts, or is Working Group "go fever" allowed to dominate?

- Do processes put evidence of solving end-user and developer problems8 ahead of groupthink and reckons?

- Do those processes allow high-quality features to ship ahead of full consensus, based on evidence?

- Do they adequately protect implementers from IPR risks?

These questions do not line up clearly with corporate jerseys. They do not favour one company's designs over another's. Google, Microsoft, Apple, and Mozilla all have fielded designs that easily pass these tests, and others that flunked. That's the thing about quality; metrics don't care about status or affiliation. Quality doesn't have a “team”, it has units of measure.

Quality tests help us evaluate features in the market-based ecosystem of voluntary standards. The presumed working mode of Web SDOs is that many ideas will be tried (responsibly, hopefully) and the best ideas should gain traction. Eventually, better designs sway the market, leading to calls for standardisation.9 Competitors who objected, even strenuously, can then adopt liberally-licensed designs, provide alternatives, or lose share. This logic does not designate grandees or smoke-filled rooms as arbiters of quality. Instead, we rely on voluntary adoption, the testable qualities of shipped designs, and developers voting with their feet.

Responsible, quality-oriented feature development processes reject priesthoods, seers, and oracles, putting evidence-based engineering in their place. This focuses us on solving problems we can see, showing our work, inviting critique, and engaging constructively.

There were never curtains from behind which a feature's essential “standardness” could be revealed, and we should not invent them because the messier, egalitarian reality of feature evolution seems disquieting. Like “Best Picture”, formal SDO status isn't a reliable indicator of quality. Each must judge for themselves.

In the end, the wider internet engineering community always decides if problems are relevant and if designs are “correct.”

There are no blinding flashes of insight, only the push and pull of competing proposals to solve user and developer needs. When standards fail to meet needs, developers patch over the gaps at great cost, or route around standards-based platforms altogether. It is no coincidence that the phases of the Blink Launch Process and tools like Origin Trials present practical steps away from Working Group mysticism. Moving, however haltingly, towards egalitarian, pluralistic collaboration has delivered tremendous progress, despite recalcitrant participants.10

What Working Groups Really Do

Along with other experienced colleagues at Google and Microsoft, I have had the privilege to teach the practice and theory of standards-track feature development to talented engineers working inside Chromium.

The role of chartered Working Groups looms large in those conversations, but it is far from central. This is because the primary job of a Working Group is to accelerate adoption of existing designs that have enough support to move forward and insulate them from IPR-based attacks. This is both their official job (per SDO process documents) and their primary value.

“I” dotting and “t” crossing is expected, and it can slightly alter designs, but chartered Working Groups never work well as venues for effectively canvassing developers for problems to solve. Nor are they good environments for testing ideas. If the goal is to solve new problems or design new solutions, chartered Working Groups are never the best forum for the simple reason that it is not what they are built to do.

Consider the most recent charters from a few lively W3C Working Groups:

Per the formal process governing charters, each group's convening document contains several sections that outline:

- A problem statement, laid out at the group's (re)charter.

- An explicit scope; i.e., technologies the group can consider in addressing that problem.

- An a priori list of documents and deliverables the WG will produce.

Everything in these charters works to provide clarity and precision about what the group will deliver because that is how members (firms, in the W3C's case) weigh up the costs and benefits of joining relative to their patent portfolios.

Yes, it's all about patents. Standards Development Organisations are, practically speaking, IPR clearing houses. From this perspective, all the hoops one must jump through to join a chartered group make sense:

-

Q: Why do companies have to officially join each Working Group separately?

A: Patents.

-

Q: Why does each participant need to be approved by a company's main W3C delegate?

A: Patents.

-

Q: Why are there so many checkpoints in the process that appear to do little more than waste time?

A: Patents.

-

Q: Why does the whole membership need to vote to progress a document to a formal standard?

A: Patents.

Features named in Working Group charters are the only designs a group can standardise, and groups run into trouble with lawyers when they exceed charter scopes, because participating firms may not have done a search in their portfolio (or their competitor's) regarding designs outside the pre-determined scope. When this happens, all progress can halt for an indeterminate amount of time. SDO processes and documents, therefore, work to cabin the risk, moving early design out of Working Groups and into other venues.

Chartered Working Groups Are Not Design Venues

All of this drives to a simple set of obvious conclusions: venues other than chartered Working Groups are necessary in order to do the sort of high-iteration-pace design work that leads to higher-quality designs.

It's a punchline that standards committees are bad at design, but this is by design. They do not have the cycles, mission, or tools needed to explore developer problems, let alone iterate towards compelling solutions. Their job, per the official process documents that convene them, is to ensure that certain quality attributes are tended to (e.g., tests and complete specifications) on the way towards licensing of the intellectual property embodied in specifications.

The Role of Incubation

To this end, internet SDOs have many alternatives that are better suited to design work, and which create glide paths for the fittest proposals into chartered Working Groups to gain eventual status as Web Standards. Here are a few:11

-

- Interest Groups

- Business Groups

- Community Groups, particularly the WICG

It's always possible for designs to fail to solve important problems, or fail to solve them well, and better designs flow naturally from a higher pace of iteration and feedback. Incubation venues tend to work better for design because they lower some strictures Working Groups erect to create patent clarity. Instead of needing to pre-define their deliverables, these groups can fail fast and iterate. When they work, they can be submitted to Working Groups to get patent and IP issues finalised.

Incubation venues display very different working modes and membership than formal Working Groups. Instead of pre-decided, formal deliverables, groups can form around nebulous problem statements and define the issues long before landing on a single design. There is no stable set of delegates from member firms, largely dominated by implementers. Rather, interest groups may form organically, even from web developers interested in shared problems. Instead of predefined timelines and pre-ordained deliverables, these groups work at the speed of their need and understanding. And instead of design pivots representing potential failure, incubation venues can test multiple alternatives. Discarding entire designs is even healthy while the furious iteration of incubation plays out.

Lower barriers to entry for web developers, along with structures that encourage dynamic problem-solving coalitions, tend to create higher pace and more focused work. This, in turn, allows consideration of more alternatives and helps facilitate the iterations that hone design. Not every Incubation venue succeeds, and not every design they consider wins. But their outsized success vs. design-in-committee approaches has been apparent for more than a decade.

Only those mistakenly wedded to, or cynically selling, mystical notions of Working Groups as diviners of revealed truth try to rubbish the web's incubation venue's outstanding track record of delivery. Given the overwhelming success of incubation, including the demonstrated benefits of fail-fast iteration, we must then ask why there are still proponents of Working Group misuse and process opacity.

No Prophecies, Only Engineering

Splitting the needs of design from the strictures of standardisation isn't against the spirit of standardisation, nor is shipping ahead of a vote by the full membership of an SDO problematic. These approaches are written into the process documents of the internet's most effective bodies. Implementation experience is required for a proposal to become a ratified standard, and Working Groups are enjoined by process from undertaking the explorations incubation venues specialise in. Which is why those same SDOs build and encourage incubation groups.

This is an uncomfortable acknowledgement for some.

Folks I have talked to seem to imagine rooms filled with people who know everything and always make correct decisions. There are no such rooms. We're all just engineers trying to solve problems, from the heights of the TAG and the Internet Architecture Board to the scrappiest W3C Community Group or IETF Bar BOF. And sometimes we get it very wrong. But that should not immobilise us in fear; it should cause us to do what we always do when engineering: adopt processes and guardrails to improve quality and increase the rate of delivery.

Problems only get solved by people of good cheer working hard to spot them,12 trying out solutions, and working collaboratively to document the ones that work best. There are no oracles in standards work, only engineers. And that's more than enough.

FOOTNOTES

While the Blink Launch Process raised the bar in some ways for every project, many parts of Blink's risk-based logic for feature leadership still lack analogues for tools like Origin Trials in other projects. Over the past decade, this has generally not been a major problem because other projects rarely lead (sadly). ⇐

And, it would seem, long-time browser engineers and standards participants. ⇐

The IETF famously phrases this principal as "rough consensus and running code", which indicates that that formal status as an official standard should be reserved for designs with experience in the market.

A frustrating fraction of the web's erstwhile friends twist the arrow of causality, demanding formal standards status before they (or anyone else) dare to ship a proposal. This is, of course, entirely backwards, but sounds convincing to web developers who desire interoperability which comes from uniform implementation status which, historically, correlates with de jure status.

This rhetorical bait-and-switch is deployed very frequently by fifth columnists. ⇐

Most contemporary web standards explainers use a template derived from a document I authored for use by Google's Web Standards engineers, and which was adopted by the W3C's Technical Architecture Group during my service there.

The current template has drifted from the original somewhat, but the initial intent is in tact: to favour the perspective of working developers over implementers when weighing up potential designs.

This explicit goal is realised through many steps of the Blink Launch Process. It's that process which forces Blink engineers to request TAG design review for new features. This combines with the reality that most new web features begin life within Chromium and Blink's “coalition of the willing”. As a result, designers of important new features experience Blink's process guardrails as the most constricting influence on quality as they work towards shipping. And one of those guardrails is to explain features in terms that web developers can understand via Explainers.

As a sociotechnical system, the Blink Launch Process, and its integrations with the TAG and various incubation bodies, are calculated to act in a Popperian mode, rejecting claims to design authority and oracular Working Group pronouncements. In their place, we explicitly delegate power to groups that have done a good job of representing wider constituencies. The goal is to place the key question "does this design solve an important problem well?" at the centre of feature development, and to trust users (web developers) as judge of the results.

We reject both essentialist and inductive intuitions about where features “should” come from, and instead require designers walk a mile in the shoes of their users. This is easiest to do in incubation venues like the WICG, where the barriers to bringing web developers into the conversation are lowest.

This also is why the Blink API OWNERS expect “Considered Alternatives” sections of explainers to be exhaustive, and that examples appear the languages developers use (HTML, CSS, and JS), not the languages implementers think in (WebIDL and C++). Domain experts may understand the system, by sympathy for the machine is not a substitute for web developers trying designs and rendering their own judgement. The Blink Launch Process guards against go fever while enabling feature designers to launch responsibly, even when forced to go first by the disinterest of other vendors in solving problems. ⇐

Even if a proposal is, for some blighted reason, floated first within a chartered Working Group, it is still only that: a proposal without any standing as a standard. It is only upon publication of a formal standard document months or years later that a proposal, encoded in a specification, can be called a Web Standard and carry any of the attendant IP protections.

That necessarily happens after the proposal has been offered, and generally happens months or years after all design work has completed and multiple interoperable implementations are fielded. ⇐

Until prompted to consider it, I had not been aware that WebP had made the transition to a formal standard in any venue. ⇐

It would, obviously, have been better for WebP to be floated at IETF many years prior, but adoption in every major engine occurred before that process began. ⇐

In that order, always. ⇐

In reality, new web features are a thinly traded market, and long experience (e.g., CSS's “prefixpocalypse") has taught the web community that uncontrolled experiments are disruptive and costly. This lesson has, in my view, been heavily over-sold.

Responsible approaches (e.g., Origin Trials) now have a long track record of success. Those who argue that we must sort out differences in perspective exclusively by thinking hard about designs within the teleconferences of chartered Working Groups have not demonstrated that their approach is superior in any way that I can see. Simply trying ideas and gathering developer feedback has, despite tremendous resistance from Apple, generated a many important and high-quality features over the past decade using this model.

Had we waited for Working Groups to recover from stupors induced by fifth columnist's disinterest, the quality of the resulting designs would not have improved substantially. Nor, in my estimation, would they be more likely to eventually achieve status as ratified and widely adopted Web Standards.

There will always be a role for chartered Working Groups to improve on extant designs, but we have falsified the thesis that it is necessary for design to happen within them. The positive qualities of successful features are not down to venue, but the constituencies involved, and the evidence used to evolve them. That developer involvement and vendor flexibility towards feedback overlapped with Working Group-centered design efforts at certain moments in the past gives rise to much confusion. New entrants, thankfully, can skip old muddles and move straight to beginning their work in more entrepreneurial, high-iteration-rate venues built for incubation. ⇐

Many big, old chartered Working Groups attract participants who are earnestly confused about the value of their own contributions or the correct scope of the group's activities. Luckily, it is not necessary to convince them that they should not have outsized power in these domains. Instead, we only need to route around by moving early design work to incubation venues that enable more productive and egalitarian practices.

There is little that hard-done-by WG delegates can do when this happens, other than to muddy the waters about what the best order of operations is. They cannot prevent design work from decamping to more fertile ground because it is in full alignment with the roles assigned to Working Groups and their feeder venues by the formal processes that govern SDOs.

Design work should never have been on their docket, and it is always illegitimate Working Groups to attempt to monopolise it. Their charters make this extremely clear. ⇐

The WHATWG is unique among internet SDOs in disavowing any sort of incubation or early design process, which largely serves to make the W3C's various appendages (particularly the WICG) more useful and vibrant. ⇐

Taking developers seriously and not being dismissive about the needs they express is the first step in this work. It is therefore extremely problematic when implementers gaslight developers or claim the needs they are taking time to express are somehow illegitimate.

There are many cases where an SDO or Working Group can't, or shouldn't, work to solve certain problems. But we can engage those questions without being dismissive, and should show our work along the way. Vendors who make a habit of brushing off developers, therefore, bring disrepute to the whole goal of standards work. ⇐

Apple's Assault on Standards

Internet enthusiasts of the previous century sometimes expressed the power of code by declaring the sovereignty of cyberspace, or that "code is law."

As odd as these claims sound today, they hit a deep truth: end-users, and even governments, lack power to re-litigate choices embodied in software. Software vendors, therefore, have power. Backed by deeply embedded control chokepoints, and without a proportional response from other interests, this control is akin to state power.

Both fear and fervour about these properties developed against a backdrop of libertarian1 attitudes toward regulation and competition. Attenuating vendor power through interoperability was, among other values, a shared foundation of collaboration for internet pioneers.

The most fervent commitment of this strain was faith in markets to sort out information distribution problems through pricing signals,2 and that view became embedded deeply into the internet's governance mechanisms.3 If competition does not function, neither do standards.

The internet's most consequential designs took competitive markets as granted. Many participants believed hardware and software markets would (and should) continue to decouple; that it would be easier for end-users to bring their own software to devices they owned. It is odd from the perspective of 2025 to suggest that swapping browsers, e.g., should come at the cost of replacing hardware. This is why Apple have worked so hard to obscure that this is exactly the situation it has engineered, to the detriment of users, the web, and internet standards.

Internet standards bodies assumed the properties of open operating systems and low-cost software replacement to such an extent that their founding documents scarcely bother to mention them.4 Only later did statements of shared values see fit to make the subtext clear.

And it has worked. Internet standards have facilitated interoperability that have blunted lock-in, outsized pricing power, and monopolistic abuses. This role is the entire point of standards at a societal level, and the primary reason that competition law carves out space for competitors to collaborate in developing them.5

But this is not purely an economic project. Standards attenuate the power of firms that might seek to arrogate code's privileges. Functional interoperability enables competition, reallocating power to users. Standardisation is therefore, at least partially a political project; one that aligns with the values of open societies:

We must ask whether ... we should not prepare for the worst leaders, and hope for the best. But this leads to a new approach to the problem of politics, for it forces us to replace the question: "Who should rule?" by the new question: "How can we so organize political institutions that bad or incompetent rulers can be prevented from doing too much damage?"

Without a counterweight, network effects allow successful tech firms to concentrate wealth and political influence. This power allows them to degrade potential competitive challenges, enabling rent extraction for services that would otherwise be commodities. This mechanism operates through (often legalised) corruption of judicial, regulatory, and electoral systems. When left to fester, it corrodes democracy itself.6

Apple has deftly used a false cloak of security and privacy to move the internet, and web in particular, toward enclosure and irrelevance. This post makes the case for why Apple should be considered a corrupted, and indeed incompetent, autocrat in our digital lives. It abuses a unique form of monopoly to extract rents, including on the last remnants of open ecosystems it tolerates.

Worse, Apple's centralisation through the App Store entrenches the positions of peer big tech firms, harming the prospects of competitors in turn. Apple have been, over the course of many years, poisonous to internet standards and the moral commitments of that grand project.7

Despite near continuous horse-race coverage in the tech press, the consequences of this regression in civic/technical affairs is not well socialised.

The Power of Interoperability

Standardisation expands the reach of interoperable technology, pushing firms to innovate, rather than extracting rents on commodities.

Interoperability-in-being gives users choice, forcing competitors to differentiate on quality and not-yet-standard features. Standards expedite interoperability by lowering the costs for implementers and reducing tails risks, e.g. from patent trolls. Over time, a complete enough set of standards can attenuate the power of vendors to extract rents and prevent progress in important domains.

Interoperability is not the only mechanism that can reduce the power of dominant firms, but it is the most powerful. Free and Open Source software (FOSS) can provide a counterweight too, but OSS is not a full solution.8

Voluntary Adoption Is Foundational to Internet Standards

Interoperability, and the economic surpluses that flow from it, are underpinned by voluntary adoption. This is enshrined in the "open stand" principles agreed to by no less than ISOC, IETF, IAB, IEEE, and the W3C.:

...

5. Voluntary Adoption

Standards are voluntarily adopted and success is determined by the market.

— The IAB, IEEE, IETF, ISOC, and W3C,

"The OpenStand Principles"

This final principle is the shortest, and many readers will understand it as a dodge; a way for Standards Development Organisations (SDOs) to avoid being seen to pick winners. But it is more than that.

Voluntary adoption is necessary for internet standards to function, and it creates a presumption of fair play.

Several implications bear mentioning.

First, the principle of voluntary adoption is necessary for effective standards development. Without a mechanism for determining which designs are better, we are unable to make consistent progress. That test never comes from within an SDO; it is always customer-defined. Writing a standard is not a test of quality, and without a functional market to test designs in, SDOs are irrelevant.

Second, this principle outlines a live-and-let-live doctrine, both within standards bodies and in the market. Participants may want their design to win, but are enjoined from procedural shenanigans to prevent competing designs from also being standardised.

Lastly, voluntary adoption marks customers (developers) and suppliers (browser vendors, etc.) as peers and creates norms of mutual respect within the walls of SDOs.

For all of these reasons, voluntary adoption must be defended, and actions taken to undermine it met with resistance and eventual sanction.

Apple's Unique Monopoly

Regulators have had no difficulty in building market tests that demonstrate the power Apple holds in the lives of users.

Some of these tests have produced comical contortions as Apple has attempted to weasel out of its responsibilities. Consider the Trinitarian claim that Safari is simultaneously one product, and also three. Or that iPadOS, despite sharing nearly all code with iOS, marketed under that brand for years, supporting identical features, running the same third-party software, releasing on the same cadence, and running exclusively on the same hardware architecture is (somehow) an entirely different product.9

But for as clear and effective as regulator's tests have been in piercing these smoke screens, they do not capture the most important aspects of Apple's influence on the market for smartphone software: the monopoly on wealth.

Apple suppresses standards-based platforms and their disruptive potential through a mechanism every software developer understands: wealthy users carry iPhones, and they have all the influence.

Competition law does not explicitly recognise this distortion of the market, but the connection between the influence of the wealthy and the choices available to other end-users is indisputable.

Despite selling fewer than a quarter of smartphones globally for the past decade, Apple has built and anti-competitively maintained a supermonopoly among the wealthiest 10-20% of the world's population who, in turn, control effectively all wealth on the planet. This has handed it control over software distribution due to the social effects of wealth. Apple pairs legitimately superior product attributes (e.g., leading chip design) with anti-user and anticompetitive tactics — e.g., green vs. blue chat bubbles, suppression of browsers — to maintain this position.

Apple has put in place a set of interlocking restrictions to ensure the web cannot disrupt native apps within this user base. Those users, in turn, warp the behaviour of software developers thanks their spending power and positions within the software industry. Developers understand that if they cannot demo their wares to bosses and VCs (all of whom are wealthy) on their own devices, their software might as well not exist.

The long-stable propensity of users who make more than $100K USD/year to carry iPhones combines with Apple's suppression of browsers and PWA capabilities to ensure developers have no choice but to build native applications. These effects were visible in population-level statistics a decade ago and have been stable ever since:

Knowing whether someone owns an iPad in 2016 allows us to guess correctly whether the person is in the top or bottom income quartile 69 percent of the time. Across all years in our data, no individual brand is as predictive of being high-income as owning an Apple iPhone in 2016.

Developers are forced into the App Store by missing web capabilities, ensuring an advantage for Apple's proprietary ecosystem. This induces wealthy and influential users to default to the App Store for software, further damping the competitiveness of open platforms.

The monopoly on influence explains why Apple is wedded to legalistic, dissembling tactics in order to prevent the spread of web apps. Should the work of internet and web standards bodies ever become relevant, Cupertino understands the market for software will transform in ways it cannot control or tax.

How Apple Uses Its Monopoly to Centralise and Enclose

Developers are forced into the App Store by a lack of functionality in browsers and web apps. By contrast, Apple has liberally meted out fingerprintable system capabilities to privacy-invading native apps. It has also allowed them to suppress pro-privacy interventions when it serves them.10

Apple professes that "privacy is a human right", but this as an attempt to turn the consequences of Apple's own largesse towards data abusers into a marketing asset. Wide-scale privacy erosion has depended, fundamentally, on Apple's own decisions, and it has not recanted.

It was Apple's choice to introduce less safe, less privacy-preserving native apps into iOS. It was also Apple's choice to deny competing browsers engines the freedom of voluntary feature adoption. This has ensured that important underlying capabilities could only ever be accessed through Apple's proprietary APIs, and only ever by those who are willing to agree to Cupertino's extractive terms.

The result has been API enclosure; appropriation of commodity capabilities that themselves are standards-based — e.g., rich graphics, USB, Bluetooth, NFC, file storage, etc. — by a proprietary ecosystem. Meanwhile, it has delayed and undermined the emergence of safe and privacy-preserving versions of those features on the web.

This, in turn, has created a winner-take-all dynamic inside the app store, harming privacy, security, and competition in the process.

Apple's Transgressions Against Voluntary Adoption

This strategy relies on interlocking policies that harm competitors, and the sabotage of voluntary standards adoption lies at its heart. A Bill of Particulars for crimes against the internet community springs from a small set of undisputed facts.

Apple has:

-

Restricted competitors from shipping their own implementations of web and internet standards, depriving them access to influential users.

-

Forced all iOS browsers to use Apple's own defective, impoverished implementation.

-

Undermined user security and privacy through iOS browser engine monoculture.

-

Used contractual terms to dissuade competitors from supporting standards Apple disfavours.

-

Objected spuriously within standards bodies to prevent standardisation of features which Apple offered no counter-proposal.11

-

Engaged in marketing and product UI that discourages use of web-based alternatives.

-

Misled regulators and the public when presented with evidence of the harm from these actions.

Through these and other overt acts, Apple has worked to disempower users, depriving them of choice by preventing open platforms from challenging native apps.12

This isn't just a fierce market participant competing aggressively. Apple has done violence to the founding ethos of internet and web standards development. Instead of honourably withdrawing from those groups, Apple has maintained a charade of engagement, and gaslights other participants while actively sabotaging the principle of voluntary adoption that internet standards rely on.

Unilateral Off-Ramps

Apple has never been forced to suppress its competitors, nor to create an anticompetitive landscape. Cupertino's senior management have intellectually consistent options that would allow it to pursue growth of the superior (we are told) native app ecosystem without threatening browser choice or the good functioning of internet standards.

Let's consider two: all safe browsers, and no browsers.

Apple could, of course, simply enable the same sort of level playing field for high-quality browsers that every competing general-purpose OS vendor has for the web's entire history. Apple itself facilitates this sort of ecosystem on macOS.13 Any plausible restrictions stemming from available system resources have long been overcome by progress in mobile hardware, particularly within Apple's ecosystem.14

The only reasonable restrictions on competing browser engines relate to security. As other vendors have generally had a better track records than Apple regarding sandboxing, incident response, patch gaps, and support for older OS versions, this should be no practical obstacle.

Lest Apple's defenders worry about the impact on Safari, recall that under true browser choice, Apple retains considerable market advantages, including (but not limited to) pre-installation, lower structural costs15, and continued differentiation through integration.16 Such bulwarks have allowed Safari to retain considerable share on macOS in spite of stiff competition and Safari's poor track record on security and standards conformance.

Alternatively, Apple could withdraw Safari while forbidding web content on iOS. This is a fully consistent position, and has been available to Apple from the moment of the App Store's release. The iPod did not include a browser, and many subsequent Apple OSes lack functional browsers. iOS and visionOS are uniquely deficient in this regard.17

Either way, the decision to undermine choice and standards rests entirely with Apple. It has always had intellectually honest solutions to the problems it has created. Apple cannot claim the situation is anyone else's fault, or that it has had no alternative.

How Apples Crimes Differ From Prior Episodes

It should be obvious that I do not consider Apple's failure to implement standards I personally approve of to rise to a level worthy of sanction.

Under voluntary implementation, every vendor is free to ship what they please, including Apple. It may be sad, or even damaging, when features go missing from important products, but that is not a calamity; it's simply an input to be priced by the market. This has traditionally been experienced as browsers gaining or losing share.

Is not enough to cite a lack of features, bungled implementations, peevish behaviour in working groups — or even rank dishonesty — as reason for censure. These are, to a greater or lesser degree, players playing the game within the rules. Certain tactics may be distasteful, but are squarely inside the "awful but lawful" zone. Standards venues should allow them, with sanctions for poor behaviour meted out in the social realm, if at all.

Apple's outrages against the community are more fundamental, and more dangerous.18

Some will see a parallel to the Paradox of Tolerance, and I do not believe this is mistaken. Standards bodies can, and should, admit many positions by their participants, but granting membership in good standing to parties who are actively uprooting the basis for standards is madness. It ensures that standards, and the ecosystems that depend on them, wither and die.

By subverting the voluntary nature of open standards, Apple has defanged them as tools for users against the totalising power of native apps in their digital lives. This high-modernist approach is antithetical to the foundational commitments of internet standards bodies and, over time, erode them.

Indeed, no other vendor has achieved what Apple has in the realm of anticompetitive suppression of the web. We must not imagine that Apple would stop at the Application layer given a chance. The same mechanism threatens voluntary feature adoption in every other layer of the stack, too.

Necessary, Proportional Responses

The web and internet communities must understand the threat and the ongoing, cumulative harm done to the web and to internet standards. It seems to me that this point has hardly been engaged, let alone won, within the walls of SDOs. But if it were, then what? What can be done?

The founding documents of internet SDOs do not include censure mechanisms for sabotage. The W3C's bylaws, for example, only relate membership in good standing with paying dues. Regardless, it is possible — and I believe urgent — to do more.

First, proposals can be raised to amend bylaws to include mechanisms for censure by votes of the membership for the kinds of outrages alleged here. These are likely to fail, and will surely be rejected at first, but the act of raising these questions has power. Bringing up these issues in plenary meetings can, at a minimum, elicit a response. That, on its own, is valuable to the community.

Next, leadership boards with moral authority can consider the question and issue guidance. The W3C's Advisory Board and Technical Architecture Group and the IETF's Internet Architecture Board have the ear of the membership, even on non-technical topics, should they choose to weigh in on the side of their own continued relevance.

Most importantly, individual delegates to Working Groups can recognise that Apple's forced monoculture is illegitimate and corrosive. They can resolve not to accept "Apple does not comment on future products" in response to questions about implementation timelines.

As long as Cupertino demands a monopoly, we must demand it take responsibility for the consequences.

Today, Apple alone chooses which features ship in WebKit, and which can be used by competing browsers. Even if it does not to enable them in Safari, it can provide more to others. It is simply illegitimate for Apple to claim that it cannot, or should not, allow other vendors to reach feature parity between their iOS browsers and other products that use their own engines.

WebKit purports to be Open Source, but in practice Apple has used it to undermine the "bring your own code" foundation of OSS. It is illogical for Apple to cite a disinterest in a feature in Safari as a reason for Apple not to be expected to implement those features in iOS's WebKit binary, making them available for other embedders to flag on.

The sham of WebKit as an Open Source project is incompatible with preventing other vendors from introducing features they would turn on for their iOS users if allowed. The destruction of voluntary adoption is not a shield against critique. Instead, it must heighten expectations. Apple agues it should be singularly entrusted with control over all web features on iOS, despite Safari and WebKit's trailing record on standards' conformance, security, and even privacy. This is nonsense, but so long as it is the law of the land in code, Apple should bear the costs.

Apple alone must be on the hook to implement any and every web platform feature shipped by any and every other engine. It does not need to enable them in Safari, but must make them available for use by others as they see fit.

So long as competing vendors are forced into the App Store and required to use Apple's engine, Cupertino owes much more when it comes to completeness and quality. So long as Cupertino compels use of WebKit, the demand should be echoed back: parity with browser features on other Operating Systems is the minimum bar.

Fundamentally, the web and internet community must stop accepting the premise that Apple should benefit from the protections and privileges of voluntary feature adoption while denying it to others.19

Lastly, and perhaps most controversially, delegates and organisations can use their positions to vote against Apple's personnel in elections to leadership positions within internet and web SDOs. It is inconsistent for Apple to hold positions of influence in organisations it works to sabotage, and fellow participants are under no obligation to pretend otherwise. Hand Apple formal or persuasive power within these groups is a mistake, and one that can be corrected without changes to bylaws.

Why Now?

In raising these questions, colleagues have invariably asked "why now? What changed?"

Beyond the threshold point that the damage is cumulative, and therefore it isn't necessary to identify specific instances to discuss the spread rot, it's fair to ask why anyone should be agitated tomorrow when they might not have been yesterday.

Most of the factors involved have indeed changed very gradually, and humans are famously poor judges of slowly emergent threats. Apple's monopoly on influence, Cupertino's post-2009 WebKit priorities, the suppression of browser competitors, and the never-ending parade of showstopping bugs are all gradually emergent factors. Despite all of this long-running, unrefuted evidence, many continue to think of Apple an ally of the web for helpful acts now more than 15 years old.

But recent events must shake us awake. Apple's petulant attempt to duck regulations, destroy the web as a competitor for good, and frame regulators for the dirty deed was shocking. In recurring misrepresentations to regulators before and since, it has dissembled about its role in suppressing the web, and through its demand for secrecy in quasi-standards processes, has worked tirelessly to cover its tracks.

Taken individually, and in ignorance of iOS's coerced WebKit use by competing browsers, forced monoculture, habitual security failures, and strategic starvation of the Safari team, these shameful acts would simply indicate another monopolist behaving badly. It is only when considered alongside the wider set of facts that the anti-standards strategy and impact become clear.

Do Standards Matter?